In last year’s award-winning movie Garage, director Lenny Abrahamson and writer Mark O’Halloran told us a few unpalatable truths about a rural Ireland where crossroads and comely maidens are part of prehistory.

The movie’s protagonist is played by comedian Pat Shortt but although he seems a stereotype of the traditional ‘Oirish’ bumpkin of the small town, the life of ‘Josie’ says much about contemporary country and village life.

Hired for a song by his yuppie classmate to run the neglected garage where he also lives, Josie is an affable, slightly simple bachelor in middle age. His life runs according to a plain routine. At the start of the summer, Josie’s boss brings along his girlfriend’s teenage son for a part-time job and their unlikely friendship allows Josie to emerge from his shell.

The local pub is a place that does not so much say ‘shebeen’ as ‘hasbeen,’ a joyless, grimy watering hole. A community’s bonds are rotting away and it is harrowing to behold. The women look tired and shabby, drinking themselves into a stupor in the presence of their children.

Josie is mocked and bullied by the local larger lout, who sneeringly informs him that the garage is soon to be sold off to make way for apartments.

But the movie’s seminal scene takes place in the solitude of the countryside. Accompanying the elderly Mr Skerrit, a depressive whose wife has abandoned him, Josie attempts to make small talk about the town. “Ah to Hell with the town!” Skerrit replies bitterly, “no such things as towns any more.”

These words seem to resonate like a curse when news of another desperate tragedy emerges from the forty shades of green.

Such as the self-destruction of the Flood family in April in Clonroche, County Wexford or that of the Dunne family in nearby Monageer almost exactly a year before. Such as the awful, squalid death of Evelyn Joel, discovered in filth in her own bedroom in Enniscorthy in early 2006. Or the Brendan O’Donnell killings or Abbey Lara.

It is not as though mental illness and murder are new innovations in rural Ireland. But, in qualitive and quantitive terms, the recent tragedies seem different.

To what extent are they aberrations? To what extent are they the inevitable result of an old social network being irresistibly corroded by globalisation?

Whatever telepathic powers possessed by tabloid journalists (‘Evil’ screamed the front page of The Sun; the Irish Daily Mail described a ‘deranged father’), it is fatuous to draw conclusions in the Flood case. We have no access into Diarmuid Flood’s psyche so we will never know.

But the marriage of Diarmuid and Lorraine was more than just a union of two attractive, successful people. It bridged the Ireland of De Valera and Ahern.

Diarmuid Flood’s family were active in the GAA. Lorraine took part in the Rose of Tralee contest in 1991. And both were Celtic Tiger success stories; the husband ran a water filtration company, the wife worked as an aerobics instructor.

At the time of writing, investigations have yielded no evidence of mental, marital or financial troubles. It would be hard to imagine a family less likely to be devoured by suicide-murder.

In the case of the Dunne family of Monageer, however, blame was swiftly laid at the door of the HSE.

It was a Monday afternoon when the bodies of Adrian and Kiara Dunne, their daughters Leanne and Shania were found dead.

Concerns had been raised for the family on Friday after Mr Dunne contacted an undertaker about a burial plot for himself and his family.

In a melancholy twist, those two staples of traditional country life attempted to intervene: the local Gardai asked the local clergy to visit. When two priests came to the house over the weekend, they got no response.

This time, official wisdom was in no doubt that this was no random, unpreventable tragedy. Senator David Norris decried an Ireland where people could shop 24-7 but did not have access to health services at the weekend.

Likewise, the dearth of social workers was invoked after the death of Evelyn Joel, a 58 year old Enniscorthy woman with multiple sclerosis in January 2006.

It was only after a third party contacted a local doctor that Ms Joel was found suffering from severe malnutrition and dehydration, weighing only four and a half stone in an upstairs bedroom of the house she shared with her daughter and her daughter’s partner.

In Ireland overall, there are only 18 social workers with specialist responsibility for caring for the elderly. Following the case, Senior Helpline reported a one fifth increase in calls, many from rural areas.

That the health services are failing vulnerable and troubled people, be they in urban or rural Ireland, is without question. That more and more of what are essentially palliative measures are needed in the first place raises questions as to what is happening in the countryside.

It has been obvious for decades that the countryside’s old infrastructure of farms and small towns that drew upon them for trade and unemployment is in retreat. But the quite menacing scale of the economic downturn will perhaps have even more profound changes there than in urban areas. Driven by the massive demand for food, the sorry end results of which we are now seeing, the average farm grew in size by one fifth in the 1990s.

However, 60 per cent of the population live outside the five major urban centres. And at the height of Celtic Tiger double digit growth in 1996-2002, rural areas did not experience growth commensurate with other areas, while the population of Dublin and its three surrounding counties grew by nearly 14 per cent per year.

According ‘Rural Ireland 2025: Foresight Perspectives,’ a study undertaken by Teagasc with the help of UCD and NUI Maynooth, the decline in farming has been offset by the boom but agricultural and production-based employment is often poorly paid. Moreover, much of the growth and employment in these areas has been due to the construction industry which is now in freefall.

The report takes into account a number of variables. Most obviously, World Trade Organisation (WTO) negotiations are likely to put pressure on the industry as trade is liberalised.

But given the increasing demand on rural space as housing, roads and other infrastructure snake outwards across the countryside, land prices will remain high. Thus, the average farmer will find it difficult to purchase land and expand his business on a scale necessary to maintain international competitiveness, except perhaps through partnership and leasing. The turbulence in the commodities markets is hitting family farms, particularly those in cereal production.

Due to lower costs, the Irish diary sector may be in a better position than other EU nations while the abolition of milk quotas may cause overall output to rise. And the turning over of land for possible biofuel production could see at least some farmers turn over pastoral land to tillage for fuel crops.

Nevertheless, the numbers of people depending on agriculture for their livelihoods is inexorably declining. By 2025, it is estimated that there will be approximately 10,000 full-time mainly diary farmers in Ireland along with 30,000 part time farmers who will derive half or more of their income from cattle and sheep production.

By that year, farming will provide employment for 70,000-100,000 people, either directly or through the agri-food industry, including processing and transport.

The Teagasc study pulls no punches on the effects of declining agricultural employment, the withdrawal of subsidies and the end of the construction-led boom: expect adverse social effects as the country and its population become predominantly suburban.

Even the environment will be changed by the withdrawal of agriculture in marginal areas of the north and west as traditional farmlands are replaced by mono-crop forestry or scrub, something already happening certain areas such as The Burren.

For just a few decades this represents a remarkable about turn: in 1950 the Irish economy was more dependent on agriculture than it had been in 1870.

But as agriculture shrinks, so the small towns of Ireland are shrinking, if not in size then certainly in character. Sentimentalising the small town culture of old, of course, is to display a very fatuous amnesia.

There are few more bitter indictments of that world and its follies than Gar O’Donnell’s empty relationship with his father, symbolic of the wasting of a younger generation forced to emigrate thanks to the stubborn and impractical mindset of its elders. That was how playwright Brian Friel depicted ‘Ballybeg’ (literally ‘small town’) in his play Philadelphia Here I Come in the mid 1960s.

Then locked in economic stagnation and cultural conservatism, the Ballbegs of today are buffeted by globalised market forces and the resultant homogenisation. The aggressive marketing and undercutting of the multi-national brands, changed travel patterns and poor infrastructure combine to increase the cost base for smaller businesses at a time of decreasing turnover.

Thus even without, for example, the proposed downsizing of An Post, long-established local shops, pubs, post offices and other small outlets are disappearing from towns and villages.

Should this matter? Pre-globalised Ireland, rural and urban, was an impoverished and restricted backwater. Nor are these trends unique to rural Ireland.The windfall has come with strings attached, strings that bind and may not necessarily be shaken loose by the end of the conspicuous consumption.

Increased criminality in the countryside is one example.

Violent death is still mainly an urban phenomenon, despite the extent to which horrors such as the Abbey Lara shootings or the killing of Traveller John Ward by Padraig Nally excited media attention. Dublin South Central is our official ‘murder capital’ according to Department of Justice figures, 83 violent killings took place there last year.

But while drug crime usually conjures up images of a track-suited denizen stalking a sink estate in Dublin or Limerick, the drug pushers of contemporary Ireland frequently live and operate well outside the main urban centres.

Not that the countryside is a good place to be a drug user. In January 2006, a leading drug treatment GP warned in The Irish Medical News that parts of rural Ireland had no GPs or pharmacies to treat drug addicts. The GP referred to a rural ‘apartheid’ in many areas due to poor infrastructure or GPs not wanting to deal with addicts.

However, the use of legal drugs is probably even more reason for concern. The same year as the Irish Medical News article on drug treatment in the countryside, HSE figures revealed that tranquiliser prescriptions amongst medical card holders had narrowly approached the one million mark.

It comes as little surprise then, to learn that a helpline set up by the HSE South, Ballyhora Development and Teagasc is receiving 325 calls per year.

Moreover, the Farm and Rural Stress Helpline’s counsellors report that the problems of stress, anxiety and depression that any city dweller might experience are compounded by the sheer isolation that exists in rural areas.

Rural decline, be it economic or societal, need not be an inexorable and terminal decay. A good example of an ameliorative measure was launched by the GAA in April and endorsed by President McAleese.

This seeks to provide a structure in the lives of elderly men in rural Ireland who are particularly vulnerable to isolation and depression.

With the freeing of trade a likely outcome of future WTO negotiations and the ending of EU subsidies, the agricultural sector will need to target specific consumer markets.

The Teagasc report comes down heavily on the weak linkage between rural economies and FDI enterprises:

“Low levels of regional innovation are related to weak institutional capacities and reflect the lack of effective operating networks between local businesses and third level colleges, research organisations, enterprise support and training agencies.”

Rectifying these inadequacies and addressing the kind of dislocation underscored by tragedies like that at Monageer requires money. But even in the current economic climate, deferring any initiatives on rural decline simply won’t do.

In Britain, studies by think tanks such as the New Economic Foundation and the Commission for Rural Committees noted that the disappearance of thousands of small outlets is creating the ‘slow death’ of rural England.

It is surely time to prevent that happening here. Otherwise the morose verdict of Mr Skerrit will turn out to have been prescient in an Ireland where “there no such things as towns any more.”

Friday, December 26, 2008

Saturday, December 13, 2008

X Marks the Spot

Early on in his race for the White House, Barack Obama told voters that the election held the opportunity to end the ‘psychodrama’ of the Baby Boomers that had long defined American politics. He certainly had a point. It is a fairly safe bet what the reaction would have been to Hillary Clinton beating him as Democrat nominee and going up against John McCain.

The rhetoric would have been as it was in 2004. All the old grudges would have resurfaced over what side of the barricades the candidate was on in the days of Nixon and Hawaii Five-O. The ‘Boomers’ may no longer be at war with their parents but they’ll always be at war with each other. The ideological map of the USA, with its latte-drinking, pro-choice coasts of blue and its gun-lovin,’ Darwin-hatin’ red interior bears testament to that.

So Obama victory is also a victory for Generation X. This broadly means the generation born between 1965 and 1980. Alright, Obama was actually born in 1961 but do four years really matter?

Alright Irish demographics differ from America’s where 46 million Generation X-ers are sandwiched between the 80 million Baby Boomers and the 46 million ‘millenials’ a.k.a. Generation Y.

We had never had armies coming home from Normandy and Okinawa to have kids after 1945. Ireland being Ireland, we got it back to front with our maternity wards crowding in the latter 1960s on the back of the Lemass-Whittaker boom, climaxing (in every sense of the word) in 1973, when more weddings took place than any other year in the Republic’s history, before or since. But globalisation is nothing new and we marked by the same cultural trends as the rest.

Obama’s foreign policy guru on the campaign trail was Irishwoman Samantha Power, born in 1970. Enough said: The West Wing is now the X-Wing.

But who are we? The much maligned ‘Slacker’ generation is caricatured as a trough of dreamy, disassociation between the peaks of savvy confidence that came before and after us. The year 1991 is generally seen as our annis mirablis. Nirvana released their zeitgeist-defining album Nevermind and Douglas Coupland wrote the novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture whose three main characters are described as “underemployed, overeducated, intensely private and unpredictable.” The same year, Richard Linklater directed and starred in the independent movie, Slacker about a group of disaffected twenty somethings wandering around Austin, Texas one of whom muses, “I may live badly, but at least I don’t have to work to do it.”

We grew up playing Atari computer games, riding BMX bikes and alternating college with dismal jobs at McDonalds and HMV. Some of us may be taken ecstasy and embraced the born again bagginess of groups like The Stone Roses or The Happy Mondays at the end of the Eighties.

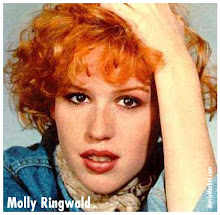

Like Molly Ringwald, star of such Generation X classics as The Breakfast Club and Pretty in Pink, we seem to have drifted into ‘where are they now?’ territory.

In last year’s bestseller, The Generation Game, David McWilliams even called us the ‘Jugglers,’ forced to juggle costs of living and now ensnared in the tentacles of negative equity and credit card debt. McWilliams does cut the Slackers some slack: “The younger generation is not some feckless bunch of hedonists who can’t do a good day’s work,” he writes. “In fact, they are the first time buyers, who have splashed out for the most expensive commuter houses in Europe, just as the market peaked in value.” Then again he was born in 1966.

He has dubbed our elders the ‘Jagger Generation’ and ‘Bono Boomers.’ The Jaggers, who make up just 14 per cent of the population, protested against nuclear energy at Carnsore Point, listened to the Horslips and unlike their squabbling cousins on the other side of the pond, are on very good terms with one another. Radicalism and Rosaries have been put aside for a consensus that is economically conservative and socially liberal. The Bono Boomers, somewhat younger, are Ireland’s true Baby Boomers, the mullet-haired lost generation of the 1980s associated with ANCO training courses and Green cards. Both became accidently enriched on the basis of a property boom and are thus cushioned against the slump.

And while it seems hardwired into the DNA of anyone whose youth straddled the Sixties and Seventies to crow that their formative years made yours look like an episode of Songs of Praise (Beatlemania, Free Love, punk rock...you so missed the boat, man), their autumnal years certainly look fun.

They are also avoiding, for now anyway, the tribulations of the country’s uppermost generational latitude, those born in the 1920s and 1930s, what is sometimes called ‘the silent generation.’ Of course, they haven’t been so silent of late with 15,000 over 70s waving placards outside Leinster House and 25,000 doing likewise in Cork. Given such revolutionary fervour, perhaps they are due a more suitable epithet: the Grey Brigades? the Geriactivists?

While recession-spurred streamlining will put many of McWilliam’s ‘Jaggers’ out of work, most of them are near retirement anyway. Moreover, it was the younger people who did all that borrowing.

Meanwhile, the bright young things with no memories of Charles Haughey or the yellow pack shelf at H. Williams also intimidate us with their sheer zest. Uniformly tall, gym-toned and kitted out in designer labels, pre Celtic Tiger penury has (so far) been something they have merely heard of.

A survey in Britain by the recruiting agency FreshMinds Talent along with Management Today found that the latest batch of young adults are more ambitious, brand conscious and more likely to change jobs than their forebears.

Even in recession, this lack of inhibition looks likely to stand to Generation Y in the way that the lack of debt will stand to the Baby Boom.

Culturally, it seems as though X was the right letter of the alphabet to affix to the current thirty and low forty somethings. Leaf through the thickest dictionary and X is done with after a few pages.

The Baby Boomers match political and economic with cultural ascendency. The most praised television shows of recent years have had Boomers balancing the crises of late middle age with the perils of power, be they James Gandolfini in The Sopranos or Martin Sheen in The West Wing.

Ed Burns, co-creator of The Wire is 62 and a Vietnam veteran. In the last two years, Hollywood has shown a 61 year old Sylvester Stallone go toe-to-toe against a much younger opponent in the boxing ring and Harrison Ford crack his whip and the notion that a sixty-plus actor cannot be an action hero.

The ‘New Hollywood’ directors of the 1970s, while technically too old (in most cases) to be Boomers, nonetheless took their artistic and political cue from this generation.

Following a long slump commencing in the 1980s, many are now enjoying an Indian summer with Martin Scorcese finally getting his Oscar for The Departed in 2006.

As for the gnarled rockers of the Sixties, people try to put them down...just because they’re still around. Furthermore, as Van Morrison reassembles the surviving musicians to perform Astral Weeks at the Hollywood Bowl, Paul McCartney defies terror threats to play an Israeli gig and Neil Young embarks on another tour, they won’t be hanging up the guitar for a few years yet.

In the realm of ‘popular’ culture, it is Generation Y that matters, especially considering how in the US, they spend $172 billion annually. Executives target them with more reality TV and the charts are dominated by the vapid creations of Simon Cowell and Louis Walsh.

We can counter that Quentin Tarantino, Beck, Marylyn Manson, Johnny Depp, Naomi Klein, Leonardo Di Caprio, Matt Damon, Kate Moss, Tiger Woods, The Mighty Boosh, Trey Parker and Matt Stone can’t be sniffed at.

But Boomers will sneer and brag that they are not in the same league as their icons and many of us will sagely nod in agreement.

Films about us like the aforementioned Slacker, High Fidelity or Reality Bites are self-deprecating while the quintessential X-er television show, Friends seems to reaffirm the stereotype of the unmotivated drifter. Just consider the lyrics of ‘I’ll be there for You’ or better still, the solo careers of the cast.

Of the two main musical legacies of Generation X, grunge and Britpop, the former has been co-opted by Generation Y in the form of ‘nu metal.’ The latter was always accused of being too derivative, as if our generation hadn’t the self confidence to be really innovative: witness Blur’s Damon Albarn and his reverence for Syd Barrett or the Gallagher brothers’ preposterous conceit that they were the avatars of Lennon and McCartney.

Of course, not all of us feel so eclipsed and it would be ageist to define people purely by their year of birth. But the moshing generation of Nirvana and Friends seems to have left a meagre stamp so far: hello, hello, hello, no show?

So let me put my fellow X-ers at ease. Our generation is old enough to have seen where the Baby Boomers went wrong and young enough not to be sidelined by Generation Y.

The current twenty some things may be the first ‘native’ surfers of the web, but who made that possible? Google was invented by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, both born in 1973 and all three of the entrepreneurs who gave the world YouTube were born before 1980.

Any child of the Seventies can remember when CB radio was the nearest you got to a mobile and MySpace was in the car park, but we evolved with the technology. Pac Man gave way to Pokemon, Rubix Cubes to YouTube.

Our parent’s generation will probably be the last one to rail against new gadgets, claiming they “are too old for that” when confronted with innovations like podcasts or Bebo.

Nor are we being infantilised by the new inventions. Most X-ers access the news online and recognise text speak as the mark of an illiterate airhead.

Accompanying the technological changes, we lived through a phenomenal social shift. Our childhoods caught the tail end of a world where the certainties of church and state were unquestioned. If you’re born circa 1970 you grow up with Sunday Mass and Holy Communion as part of life’s unalterable cycle. But in your adolescence you witness the abortion and divorce referenda and that final, futile act of muscle-flexing by the forces of Catholic conservatism. Then, as you hit young adulthood, the X Case breaks. Soon after, Bishop Eamon Casey and Fr Michael Cleary are outed as heterosexuals.

Thus the majority of Generation X believes faith should be private and contraception should be public.

After all, many of us came to sexual maturity when the ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ posters were going up. None of the fondly recalled love-ins of Boomer youth had a cloaked figure standing nearby brandishing a scythe marked ‘HIV.’ And despite the crude ‘gay plague’ propaganda that accompanied the arrival of that awful disease; if you’re gay, there are few safer places to be than in the company of Generation X-ers.

Politically, meanwhile, our generation has learnt to be pragmatic. Listening to some Sixties veteran bemoan the youthful ‘radicalism’ that seemed to peter out after the Vietnam War often sounds less like generational, than sibling rivalry. In that respect, we look like the sensible but overlooked middle child, sandwiched between the eldest, confident and self-righteous, and the youngest, noisy and spoilt. And though many former hippies are convinced they hold a monopoly on idealism, this is, frankly, a delusion.

Yes, the fertility rights of today’s women owe much to the ‘Condom Train’ and activism of those women including the recently deceased June Levine. Yes, there were marches for Civil Rights. Yes, racism and the notion of blameless American foreign policy became discredited.

But it has to be asked how many of those changes were coming anyway in western societies. In Swinging Sixties Britain, for example, changes to the law on homosexuality, divorce and capital punishment were pushed through, not by student demos, but by an elderly Nonconformist academic, Sir John Wolfenden and a liberal Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins.

When the United States got its first Baby Boom President, Bill Clinton, not only did he fail to bring about universal health care for Americans, he introduced ‘welfare to work’ and ‘three strikes and you’re out’ anti-criminal legislation that must had deceased Sixties radicals like Huey Newton and Abbie Hoffman cart wheeling in their graves.

When UCD’s Belfield campus was first designed in the late Sixties, the space between the faculties and lake were arranged in ascending layers to preclude large numbers of revolutionary longhairs assembling in one place, as they had recently been doing at the LSE and Sorbonne. But the careers of student lefties like Ruairi ‘Ho Chi’ Quinn and Pat Rabitte have been proof that they could have made do with Trinity-style cobbles.

So we have less to sell out. And when your adolescence coincides with communism being buried in the rubble of the Berlin Wall, it is very hard to muster enthusiasm for utopian politics.

Then again, we have little admiration for the mercenary chic of the yuppie Eighties either. We saw the social disruption and plain nastiness it brought about. Some of our less affluent members experienced it. Che Guevara may not be a Slacker icon, but neither is Margaret Thatcher.

Of course the Iron Lady was notorious for declaring there was “no such thing as society.” Mobiles in hand, utterly disinterested in politics and ravenous for updates on Britney and Posh, the brash young consumers of Generation Y have done her proud.

So to sum it all up, we are adaptable to changing technology, sceptical of dogma, sexually liberated and aren’t about to carry college battle positions into middle age and beyond.

And those qualities may be just what are needed given our messed up inheritance. To quote our most celebrated martyr, Kurt Cobain: “Load up on guns and bring your friends.”

As capitalism as we knew it goes into meltdown, we are probably kissing goodbye to the one thing uniting those two smug generations that bookend us: a culture of rampant self entitlement. We can take nothing for granted now. The last thing our world needs is reckless hedonists at the helm.

So Boomers and millennials disdain us at your peril. The X-ers may be your salvation.

The rhetoric would have been as it was in 2004. All the old grudges would have resurfaced over what side of the barricades the candidate was on in the days of Nixon and Hawaii Five-O. The ‘Boomers’ may no longer be at war with their parents but they’ll always be at war with each other. The ideological map of the USA, with its latte-drinking, pro-choice coasts of blue and its gun-lovin,’ Darwin-hatin’ red interior bears testament to that.

So Obama victory is also a victory for Generation X. This broadly means the generation born between 1965 and 1980. Alright, Obama was actually born in 1961 but do four years really matter?

Alright Irish demographics differ from America’s where 46 million Generation X-ers are sandwiched between the 80 million Baby Boomers and the 46 million ‘millenials’ a.k.a. Generation Y.

We had never had armies coming home from Normandy and Okinawa to have kids after 1945. Ireland being Ireland, we got it back to front with our maternity wards crowding in the latter 1960s on the back of the Lemass-Whittaker boom, climaxing (in every sense of the word) in 1973, when more weddings took place than any other year in the Republic’s history, before or since. But globalisation is nothing new and we marked by the same cultural trends as the rest.

Obama’s foreign policy guru on the campaign trail was Irishwoman Samantha Power, born in 1970. Enough said: The West Wing is now the X-Wing.

But who are we? The much maligned ‘Slacker’ generation is caricatured as a trough of dreamy, disassociation between the peaks of savvy confidence that came before and after us. The year 1991 is generally seen as our annis mirablis. Nirvana released their zeitgeist-defining album Nevermind and Douglas Coupland wrote the novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture whose three main characters are described as “underemployed, overeducated, intensely private and unpredictable.” The same year, Richard Linklater directed and starred in the independent movie, Slacker about a group of disaffected twenty somethings wandering around Austin, Texas one of whom muses, “I may live badly, but at least I don’t have to work to do it.”

We grew up playing Atari computer games, riding BMX bikes and alternating college with dismal jobs at McDonalds and HMV. Some of us may be taken ecstasy and embraced the born again bagginess of groups like The Stone Roses or The Happy Mondays at the end of the Eighties.

Like Molly Ringwald, star of such Generation X classics as The Breakfast Club and Pretty in Pink, we seem to have drifted into ‘where are they now?’ territory.

In last year’s bestseller, The Generation Game, David McWilliams even called us the ‘Jugglers,’ forced to juggle costs of living and now ensnared in the tentacles of negative equity and credit card debt. McWilliams does cut the Slackers some slack: “The younger generation is not some feckless bunch of hedonists who can’t do a good day’s work,” he writes. “In fact, they are the first time buyers, who have splashed out for the most expensive commuter houses in Europe, just as the market peaked in value.” Then again he was born in 1966.

He has dubbed our elders the ‘Jagger Generation’ and ‘Bono Boomers.’ The Jaggers, who make up just 14 per cent of the population, protested against nuclear energy at Carnsore Point, listened to the Horslips and unlike their squabbling cousins on the other side of the pond, are on very good terms with one another. Radicalism and Rosaries have been put aside for a consensus that is economically conservative and socially liberal. The Bono Boomers, somewhat younger, are Ireland’s true Baby Boomers, the mullet-haired lost generation of the 1980s associated with ANCO training courses and Green cards. Both became accidently enriched on the basis of a property boom and are thus cushioned against the slump.

And while it seems hardwired into the DNA of anyone whose youth straddled the Sixties and Seventies to crow that their formative years made yours look like an episode of Songs of Praise (Beatlemania, Free Love, punk rock...you so missed the boat, man), their autumnal years certainly look fun.

They are also avoiding, for now anyway, the tribulations of the country’s uppermost generational latitude, those born in the 1920s and 1930s, what is sometimes called ‘the silent generation.’ Of course, they haven’t been so silent of late with 15,000 over 70s waving placards outside Leinster House and 25,000 doing likewise in Cork. Given such revolutionary fervour, perhaps they are due a more suitable epithet: the Grey Brigades? the Geriactivists?

While recession-spurred streamlining will put many of McWilliam’s ‘Jaggers’ out of work, most of them are near retirement anyway. Moreover, it was the younger people who did all that borrowing.

Meanwhile, the bright young things with no memories of Charles Haughey or the yellow pack shelf at H. Williams also intimidate us with their sheer zest. Uniformly tall, gym-toned and kitted out in designer labels, pre Celtic Tiger penury has (so far) been something they have merely heard of.

A survey in Britain by the recruiting agency FreshMinds Talent along with Management Today found that the latest batch of young adults are more ambitious, brand conscious and more likely to change jobs than their forebears.

Even in recession, this lack of inhibition looks likely to stand to Generation Y in the way that the lack of debt will stand to the Baby Boom.

Culturally, it seems as though X was the right letter of the alphabet to affix to the current thirty and low forty somethings. Leaf through the thickest dictionary and X is done with after a few pages.

The Baby Boomers match political and economic with cultural ascendency. The most praised television shows of recent years have had Boomers balancing the crises of late middle age with the perils of power, be they James Gandolfini in The Sopranos or Martin Sheen in The West Wing.

Ed Burns, co-creator of The Wire is 62 and a Vietnam veteran. In the last two years, Hollywood has shown a 61 year old Sylvester Stallone go toe-to-toe against a much younger opponent in the boxing ring and Harrison Ford crack his whip and the notion that a sixty-plus actor cannot be an action hero.

The ‘New Hollywood’ directors of the 1970s, while technically too old (in most cases) to be Boomers, nonetheless took their artistic and political cue from this generation.

Following a long slump commencing in the 1980s, many are now enjoying an Indian summer with Martin Scorcese finally getting his Oscar for The Departed in 2006.

As for the gnarled rockers of the Sixties, people try to put them down...just because they’re still around. Furthermore, as Van Morrison reassembles the surviving musicians to perform Astral Weeks at the Hollywood Bowl, Paul McCartney defies terror threats to play an Israeli gig and Neil Young embarks on another tour, they won’t be hanging up the guitar for a few years yet.

In the realm of ‘popular’ culture, it is Generation Y that matters, especially considering how in the US, they spend $172 billion annually. Executives target them with more reality TV and the charts are dominated by the vapid creations of Simon Cowell and Louis Walsh.

We can counter that Quentin Tarantino, Beck, Marylyn Manson, Johnny Depp, Naomi Klein, Leonardo Di Caprio, Matt Damon, Kate Moss, Tiger Woods, The Mighty Boosh, Trey Parker and Matt Stone can’t be sniffed at.

But Boomers will sneer and brag that they are not in the same league as their icons and many of us will sagely nod in agreement.

Films about us like the aforementioned Slacker, High Fidelity or Reality Bites are self-deprecating while the quintessential X-er television show, Friends seems to reaffirm the stereotype of the unmotivated drifter. Just consider the lyrics of ‘I’ll be there for You’ or better still, the solo careers of the cast.

Of the two main musical legacies of Generation X, grunge and Britpop, the former has been co-opted by Generation Y in the form of ‘nu metal.’ The latter was always accused of being too derivative, as if our generation hadn’t the self confidence to be really innovative: witness Blur’s Damon Albarn and his reverence for Syd Barrett or the Gallagher brothers’ preposterous conceit that they were the avatars of Lennon and McCartney.

Of course, not all of us feel so eclipsed and it would be ageist to define people purely by their year of birth. But the moshing generation of Nirvana and Friends seems to have left a meagre stamp so far: hello, hello, hello, no show?

So let me put my fellow X-ers at ease. Our generation is old enough to have seen where the Baby Boomers went wrong and young enough not to be sidelined by Generation Y.

The current twenty some things may be the first ‘native’ surfers of the web, but who made that possible? Google was invented by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, both born in 1973 and all three of the entrepreneurs who gave the world YouTube were born before 1980.

Any child of the Seventies can remember when CB radio was the nearest you got to a mobile and MySpace was in the car park, but we evolved with the technology. Pac Man gave way to Pokemon, Rubix Cubes to YouTube.

Our parent’s generation will probably be the last one to rail against new gadgets, claiming they “are too old for that” when confronted with innovations like podcasts or Bebo.

Nor are we being infantilised by the new inventions. Most X-ers access the news online and recognise text speak as the mark of an illiterate airhead.

Accompanying the technological changes, we lived through a phenomenal social shift. Our childhoods caught the tail end of a world where the certainties of church and state were unquestioned. If you’re born circa 1970 you grow up with Sunday Mass and Holy Communion as part of life’s unalterable cycle. But in your adolescence you witness the abortion and divorce referenda and that final, futile act of muscle-flexing by the forces of Catholic conservatism. Then, as you hit young adulthood, the X Case breaks. Soon after, Bishop Eamon Casey and Fr Michael Cleary are outed as heterosexuals.

Thus the majority of Generation X believes faith should be private and contraception should be public.

After all, many of us came to sexual maturity when the ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ posters were going up. None of the fondly recalled love-ins of Boomer youth had a cloaked figure standing nearby brandishing a scythe marked ‘HIV.’ And despite the crude ‘gay plague’ propaganda that accompanied the arrival of that awful disease; if you’re gay, there are few safer places to be than in the company of Generation X-ers.

Politically, meanwhile, our generation has learnt to be pragmatic. Listening to some Sixties veteran bemoan the youthful ‘radicalism’ that seemed to peter out after the Vietnam War often sounds less like generational, than sibling rivalry. In that respect, we look like the sensible but overlooked middle child, sandwiched between the eldest, confident and self-righteous, and the youngest, noisy and spoilt. And though many former hippies are convinced they hold a monopoly on idealism, this is, frankly, a delusion.

Yes, the fertility rights of today’s women owe much to the ‘Condom Train’ and activism of those women including the recently deceased June Levine. Yes, there were marches for Civil Rights. Yes, racism and the notion of blameless American foreign policy became discredited.

But it has to be asked how many of those changes were coming anyway in western societies. In Swinging Sixties Britain, for example, changes to the law on homosexuality, divorce and capital punishment were pushed through, not by student demos, but by an elderly Nonconformist academic, Sir John Wolfenden and a liberal Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins.

When the United States got its first Baby Boom President, Bill Clinton, not only did he fail to bring about universal health care for Americans, he introduced ‘welfare to work’ and ‘three strikes and you’re out’ anti-criminal legislation that must had deceased Sixties radicals like Huey Newton and Abbie Hoffman cart wheeling in their graves.

When UCD’s Belfield campus was first designed in the late Sixties, the space between the faculties and lake were arranged in ascending layers to preclude large numbers of revolutionary longhairs assembling in one place, as they had recently been doing at the LSE and Sorbonne. But the careers of student lefties like Ruairi ‘Ho Chi’ Quinn and Pat Rabitte have been proof that they could have made do with Trinity-style cobbles.

So we have less to sell out. And when your adolescence coincides with communism being buried in the rubble of the Berlin Wall, it is very hard to muster enthusiasm for utopian politics.

Then again, we have little admiration for the mercenary chic of the yuppie Eighties either. We saw the social disruption and plain nastiness it brought about. Some of our less affluent members experienced it. Che Guevara may not be a Slacker icon, but neither is Margaret Thatcher.

Of course the Iron Lady was notorious for declaring there was “no such thing as society.” Mobiles in hand, utterly disinterested in politics and ravenous for updates on Britney and Posh, the brash young consumers of Generation Y have done her proud.

So to sum it all up, we are adaptable to changing technology, sceptical of dogma, sexually liberated and aren’t about to carry college battle positions into middle age and beyond.

And those qualities may be just what are needed given our messed up inheritance. To quote our most celebrated martyr, Kurt Cobain: “Load up on guns and bring your friends.”

As capitalism as we knew it goes into meltdown, we are probably kissing goodbye to the one thing uniting those two smug generations that bookend us: a culture of rampant self entitlement. We can take nothing for granted now. The last thing our world needs is reckless hedonists at the helm.

So Boomers and millennials disdain us at your peril. The X-ers may be your salvation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)